Those of you who are familiar with the Heidelberg Catechism will know that the Catechism explicitly adopts a threefold structure in its treatment of Christian doctrine, as laid out in Question 2:

Question 2. How many things are necessary for thee to know, that thou, enjoying this comfort, mayest live and die happily?

Answer: Three; the first, how great my sins and miseries are; the second, how I may be delivered from all my sins and miseries; the third, how I shall express my gratitude to God for such deliverance.

These three things are often summarized as “guilt, grace, and gratitude”.

Now, how might the Old Testament ceremonial law have anything to do with the above? With the ceremonial law having been fulfilled and abolished in the work of Christ (Col. 2:14, 16; Dan. 9:27; Eph. 2:15-16), some may wonder whether it is still of any benefit to us when we read of it in the Old Testament. The Belgic Confession helps us in this regard:

Article 25: The Fulfillment of the Law

We believe that the ceremonies and symbols of the law have ended with the coming of Christ, and that all foreshadowings have come to an end, so that the use of them ought to be abolished among Christians. Yet the truth and substance of these things remain for us in Jesus Christ, in whom they have been fulfilled.

Nevertheless, we continue to use the witnesses drawn from the law and prophets to confirm us in the gospel and to regulate our lives with full integrity for the glory of God, according to his will.

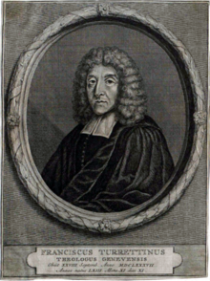

The Confession states that “we continue to use the witness drawn from the law and prophets to confirm us in the gospel…”. In this line, Francis Turretin (1623-1687) demonstrates how “guilt, grace, and gratitude” were exhibited in the Old Testament ceremonial law:

“With regard to the covenant of grace, there was a use of the law to show its necessity by a demonstration of sin and of human misery; of its truth and excellence by a shadowing forth of Christ and his offices and benefits; to seal his manifold grace in its figures and sacraments; to keep up the expectation and desire of him by that laborious worship and by the severity of its discipline to compel them to seek him; and to exhibit the righteousness and image of the spiritual worship required by him in that covenant. Undoubtedly three things are always to be specially inculcated upon man: (1) his misery; (2) God’s mercy; (3) the duty of gratitude: what he is by nature; what he has received by grace; and what he owes by obedience. These three things the ceremonial law set before the eyes of the Israelites, since ceremonies included especially these three relations. The first inasmuch as they were appendices of the law and the two others as sacraments of evangelical grace. (a) There were confessions of sins, of human misery and of guilt contracted by sin (Col. 2:14; Heb.10:1-3). (b) Symbols and shadows of God’s mercy and of the grace to be bestowed by Christ (Col. 2:17; Heb. 9:13, 14). (c) Images and pictures of duty and of the worship to be paid to God in testimony of a grateful mind (Rom. 12:1). Misery engendered in their minds humility; mercy, solace; and the duty of gratitude, sanctification. These three were expressly designated in the sacrifices. For as they were a “handwriting” on the part of God (Col. 2:14) representing the debt contracted by sin, so they were a shadow of the ransom (lytrou) to be paid by Christ (Col. 2:17, Heb. 10:5, 10) and pictures of the reasonable (latreias logikēs) and gospel worship to be given to God by believers (Rom. 12:1; 1 Pet. 2:5).”

– Francis Turretin (1623-1687), Institutes of Elenctic Theology, XI.24.9