Basil the Great (c. 329-379), in Letter 234, argues that we cannot know God in his essence, as he is in himself, since he infinitely transcends us and dwells in light inapproachable. We can, however, know God by his revealed attributes. This is reminiscent of later distinctions between archetypal theology, or God’s perfect and infinite self-knowledge, and ectypal theology, or our finite knowledge of God derived from divine revelation. (See this previous post from Richard A. Muller):

“Do you worship what you know or what you do not know? If I answer, I worship what I know, they immediately reply, What is the essence of the object of worship? Then, if I confess that I am ignorant of the essence, they turn on me again and say, So you worship you know not what. I answer that the word to know has many meanings. We say that we know the greatness of God, His power, His wisdom, His goodness, His providence over us, and the justness of His judgment; but not His very essence. The question is, therefore, only put for the sake of dispute. For he who denies that he knows the essence does not confess himself to be ignorant of God, because our idea of God is gathered from all the attributes which I have enumerated. But God, he says, is simple, and whatever attribute of Him you have reckoned as knowable is of His essence. But the absurdities involved in this sophism are innumerable. When all these high attributes have been enumerated, are they all names of one essence? And is there the same mutual force in His awfulness and His loving-kindness, His justice and His creative power, His providence and His foreknowledge, and His bestowal of rewards and punishments, His majesty and His providence? In mentioning any one of these do we declare His essence? If they say, yes, let them not ask if we know the essence of God, but let them enquire of us whether we know God to be awful, or just, or merciful. These we confess that we know. If they say that essence is something distinct, let them not put us in the wrong on the score of simplicity. For they confess themselves that there is a distinction between the essence and each one of the attributes enumerated. The operations are various, and the essence simple, but we say that we know our God from His operations, but do not undertake to approach near to His essence. His operations come down to us, but His essence remains beyond our reach.”

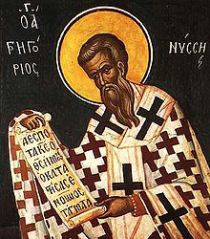

Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-395) argues along the same lines in Against Eunomius 2.3., while adding that, while not being able to comprehend the essence of God, the knowledge of God which has actually been bestowed upon us by divine revelation is sufficient for our salvation:

“And by this deliverance the Word seems to me to lay down for us this law, that we are to be persuaded that the Divine Essence is ineffable and incomprehensible: for it is plain that the title of Father does not present to us the Essence, but only indicates the relation to the Son. It follows, then, that if it were possible for human nature to be taught the essence of God, He “who will have all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim. 2:4) would not have suppressed the knowledge upon this matter. But as it is, by saying nothing concerning the Divine Essence, He showed that the knowledge thereof is beyond our power, while when we have learned that of which we are capable, we stand in no need of the knowledge beyond our capacity, as we have in the profession of faith in the doctrine delivered to us what suffices for our salvation.”